Okay, here I was in New York City, doing the starving artist routine. I was scared. Fred, my high school friend—actually, the guy I had constantly argued with when we worked together on the school paper, The Axe—took me to Columbia University and introduced me around. Within a day I had four job offers for secretarial positions. I accepted that of assistant to the Development Officer, Carol Burton, at the School of General Studies, because she said I could come in a bit late on Tuesdays, when I was going downtown to take my clarinet lesson.

Things started to fall into place. Working at Columbia offered an unexpected benefit—access to practice rooms up the street at Teacher’s College. Teacher’s College, I discovered, had a cafeteria with functional and cheap dinners, so after finishing work at 4 or 5 p.m. I headed up to 120th and ate, then practiced until maybe 11 p.m., when I walked home down Broadway. I was getting along fine with Fred and his two apartment mates, resulting in an invitation to stay, because their fourth paying student had just moved out. I had my own room—what had been the maid’s room, quite small, but complete with a tiny bathroom, with a pull-chain toilet, and a footed, ceramic bathtub. My share of the rent was $90. I got a free bed frame and a $5 mattress when a nearby hospital chucked out things they were replacing onto the sidewalk. A trip to the hardware store later, I had black enamel paint to spruce up the bed frame, and book shelves up on the wall. A trip down to 14th street later, and I had fabric at $1 a yard to make myself a bedspread and a curtain for my window that opened onto the elevator shaft. I was buying Frank Kaspar mouthpieces for $20 from the maker himself, and four boxes of reeds at Terminal Music cost me $15.30!

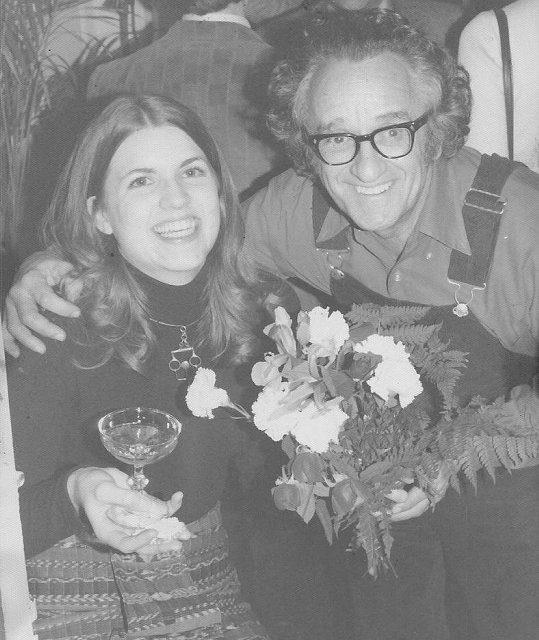

As things were settling in on the home front, I almost had cardiac arrest in my first lesson. I trekked down to 1595 Broadway on the #1 IRT one Tuesday morning and found the dingy elevator in what looked and smelled like a red-light district. I found Russianoff’s studio on the second floor, as described, chocked full of books, music, pictures, memorabilia, and usually a student or two. Leon (as he preferred to be called) was electric!–full of energy and enthusiasm. But in my first lesson, I shall never forget the pit in my stomach when he said “Let’s see how you read, honey,” and on the stand appeared the Martino “Set for Clarinet!” For those of you who don’t know the work, it opens with a fast, chromatic, finger-bending riff from the bottom of the clarinet up to the top. I had never seen the piece before, and my embarrassment was such that I was tempted to take the train out to Kennedy and fly back home.

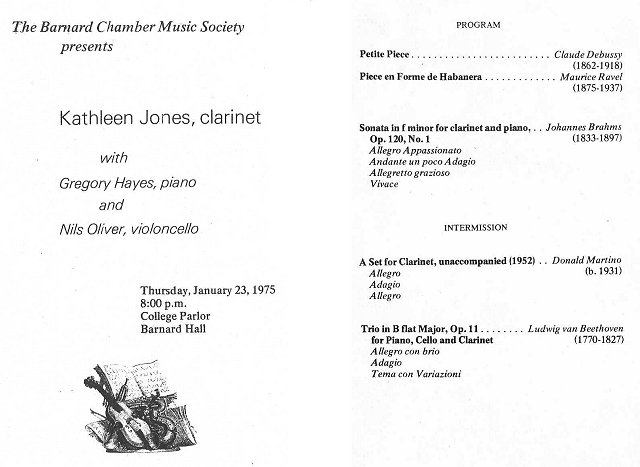

But Leon, being Leon, said something forgiving, and when my hour was up I headed back up to the School of General Studies, resolved to learn that piece!! In fact, I played the Martino Set in a recital I gave on January 23rd in College Parlor under the auspices of the Barnard Chamber Music Society, and also for my audition for Juilliard in February, with Leon, Stanley Drucker and Joe Allard on the jury. Juilliard accepted me to start a masters degree in clarinet performance in September of 1975. Ah, sweet revenge!

My year was full of wonderful classes—Leon often said “I have the greatest students in the world!” and his enthusiasm was genuine. Besides the confidence-building, he offered fabulous exercises for technique, and liberal exhortations to make music, not just play notes. He always had us record our lessons, using a cassette recorder he kept next to his chair; I still have all my old tapes, and the notebooks with exercises and annotations from each class. He invited all of his students (from Juilliard, Manhattan and wherever) over to his apartment periodically for parties (musicales) hosted by him and his wife, Penny. (She appeared as the psychologist in the film “An Unmarried Woman.” She was a practicing psychologist in real life, and Leon loved her dearly. She was about a foot taller than he, and he used to say there were only two things he wouldn’t do for her—help her on with her coat, and hold an umbrella for her.) The parties included music-making and lots of laughter. Students at that time included Rob Yamins, David Krakauer, Tim Perry, Laura Flax, Jean Copperrud, David Neithhamer and countless others. We felt like one big family.

I presented a second recital in Barnard’s College Parlor (a lovely room with a nice grand piano) on May 8th with my Music Academy friends cellist Kathy Murphy, pianist Martha Krasnican, and violist Jeff Showell, who came down from Eastman to play with me.

Culturally, I was in heaven. When my Great Aunt Hazel sent $100 to go to the opera, Fred and I went to the Met to see Boris Godunov. The Berlin Phil came to town with van Karajan conducting, and I got a seat in Carnegie Hall for Brahms 3rd and 4th Symphonies. With four other students I played woodwind quintets; the oboist was a Juilliard student and I remember going with her to a concert at Juilliard in April of 1975. “Ein Heldenleben” was programmed, and she whispered to me that the concertmaster, Guillermo Figueroa, was a fantastic violinist, who said his family was like the musical Mafia in Puerto Rico. He had a huge afro, and Strauss’ tone poem gave him ample opportunity to show why Jessica spoke so highly of him.

My teacher from Seattle, Mr. McColl, wrote that he had recommended me for a job in Puerto Rico and that I should contact the contractor, Loren Glickman, whose number I could find in the Local 802 Union directory under bassoon. I called Mr. Glickman, who told me that the job for clarinet was going to be contracted from Puerto Rico. I said thanks, and didn’t give it another thought.

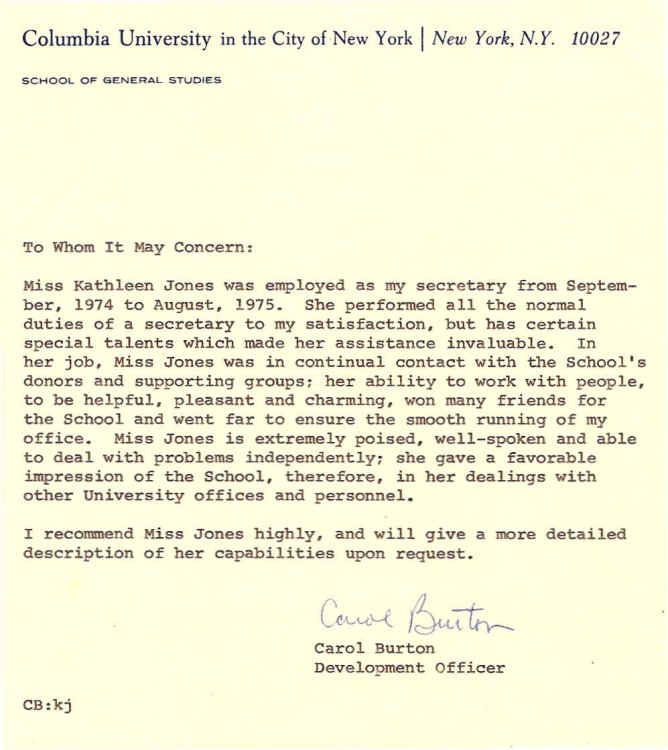

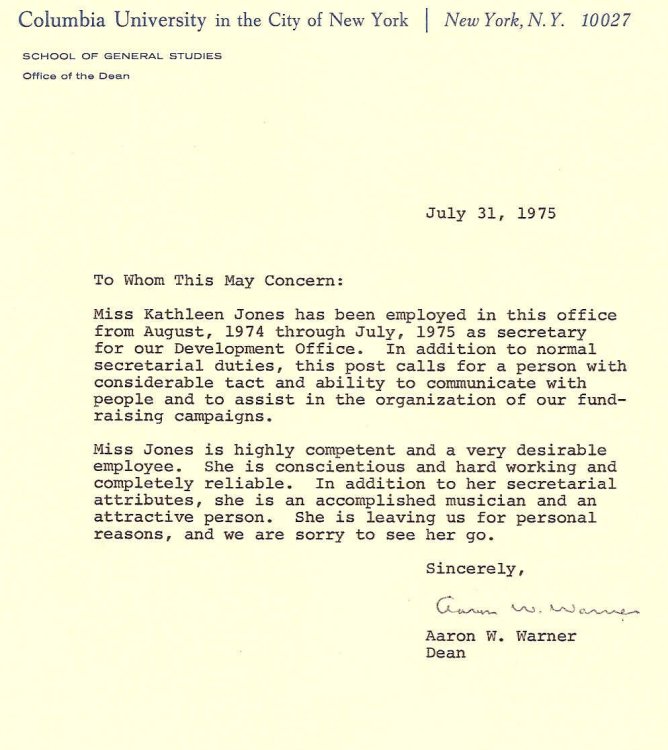

My work situation was a real opportunity for personal growth. I hadn’t realized when I accepted the job that the Development Officer was the one responsible for fund raising. Soon I was meeting and working with lovely people who were devoted to the School of General Studies because it had offered them (mostly married, middle-aged women with grown children) the opportunity to earn a bachelors degree at a later-than-normal time in their lives. Columbia University had offered them inspiring classes and a prestigious faculty; their gratitude was demonstrated through our office. “The ladies,” as Carol called them, were good intentioned and wealthy. One of our donors left in the winter for her other home in Barbados. I was working with a segment of society to which I hadn’t ever been exposed. I learned much from “the ladies,” and they were very kind to me.

I had decided that although I was having many valuable experiences, I really needed to be back in school. When my Juilliard acceptance letter arrived in the spring, I started planning to leave my job, take out student loans, and go back to an environment where I could play in an orchestra, participate in chamber groups, and practice more than the nocturnal hours currently available to me.

I gave notice to my boss, Carol, who had been so supportive during that year. Here are the much appreciated letters of recommendation written by her, and the Dean of the School, Dr. Aaron Warner upon my leaving. In July I headed out west to give some recitals and see my family, before digging in to start the masters program in the fall.

One last anecdote—part of the Juilliard process was an audition for placement in a school orchestra. At the appointed hour I was there and played my prepared excerpts for the conductor in charge. Then he put up Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel and pointed to the last-page triplet section as sight reading. I fumbled through it—it is fast and chromatic and hard to read—he asked me to try it again to get a few more of the notes. I replied “I got all the notes.” He started to protest, and I answered “I got all the notes, they were just in the wrong order.” He laughed so hard I thought he was going to fall off his chair. Yea, comic relief!!!!